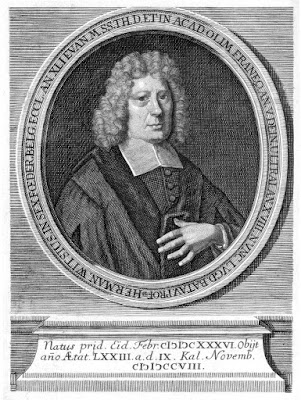

Gisbertus Voetius [Gijsbert Voet] (1589-1676)

A Short Biography of Gisbertus Voetius (1589 – 1676)

Voetius not only overlapped with Witsius for 40 odd years, but he was an important subject in the Dutch Reformed world in which Witsius lived and breathed. Not only was Witsius heavily influenced by Voetius, but Witsius’ own work was – in a sense – an attempt to reconcile the best of Voetius and Cocceius and their respective methodologies. Any careful study into Witsius must grapple with Gijsbert Voet, and hopefully the following biography presents a clear albeit brief look into this important Dutch father.

Biography of Voetius

Born in the small fortified city of Heusden as the son of Paulus Voet and Maria de Jongeling, Gisbertus (or Gijsbert) Voetius’s early years were dominated by the experience of war. Heusden was on the front line in both a military and a religious sense, as it was situated on the southern bank of the river Meuse that would later form the borderline dividing Catholic and Protestant parts of the country. Voetius’s relatives were directly involved in the conflict with Spain. Grandfather Nicolaas Dirkszoon Voet, heir to a Westphalian noble family, died in prison in ’s Hertogenbosch where he was kept on account of his support of William the Silent. Several members of Gijsbert’s mother’s family would flee the city, leaving all their possessions behind in order to accompany the Prince of Orange to Breda. Voetius’s father meanwhile saw his own property being demolished in the rampage around Heusden. Having joined the State militias for a second time in 1592, he was killed in the siege of Bredevoort in 1597, leaving behind the sickly Maria with four children.

Gijsbert was then only eight and went to live with the local blacksmith, expenses being defrayed by the city government. Noticing his excellence in the study of letters, the Heusden magistrates decided to prolong their sustenance. In 1604 they sent their youngster – of small stature, but intellectually mature – as ‘the city’s student’ to the Leiden State College. Voetius seems to have felt at home there. The daily readings of the Scriptures and the Heidelberg Catechism as well as the College’s propaedeutic courses in philosophy doubtlessly contributed to his later belief in the importance of a well-defined body of student material, such as it appears in his Exercitia et bibliotheca studiosi theologiae of 1644. In philosophy, Voetius showed a special predilection for the works of Bartholomaeus Keckermann (1571–1609), but his philosophical schooling was far from one-sided. Together with fellow students such as Simon Episcopius and Caspar Barlaeus, both of whom, like his professor in logic Petrus Bertius, would later become champions of the Arminian cause, Voetius read a huge amount of ancient literature. He studied Lucretius’s De rerum natura alongside Aristotelian, Stoic and neo-Stoic classics of physics, ethics and psychology, and also read more recent works on medicine, natural history and geography. He further exercised his mathematical skills, attended chemical and anatomical experiments, and is said to have learned to play the zither, the organ and the flute.

Yet of most concern to anyone attending Leiden courses in theology during these years was the question of Calvinist dogmatics and its foundation in neo-scholastic metaphysics. The question of divine grace and human freedom divided the followers of Jacobus Arminius and Franciscus Gomarus and called for a close reading of the relevant philosophical background. Treating philosophical questions with the help of Iberian commentaries on Aristotle, Voetius’s professor of philosophy Gilbertus Jacchaeus had been warned in 1607 to abstain from dealing with theological questions. This did not mean that Catholic philosophers would become less thoroughly read. Indeed, as Bertius reproached Franciscus Gomarus in 1610: ‘Who is it, then, that every day still cites Durandus, Gabriel Biel, Molina, Bonaventura, Cumelus, Dominicus Bañez, C. Javellus, Gregory of Valentia, and others besides these?’ (Aen-spraeck, p. 26.) Bertius’s list indicates that the Leiden battle over the question of freedom and grace was fought along the same lines as that which had divided Jesuits and Dominicans during the controversies De Auxiliis within the Roman Catholic Church. Quoting Catholic authors was an accepted strategy in both the Arminian and the Gomarist camps. Many years later, Gisbertus’s eldest son, the philosopher-lawyer Paul Voet, would continue to praise the Dominicans for their ‘safe way’ in theology against the ‘common’ Jesuit enemy (Prima Philosophia Reformata, p. 2). Indeed, both Calvinists and Dominicans regarded the Jesuit search for a concordia between divine grace and human will as a shaky compromise prompted by an intellectual lack of nerve: ‘We do not go for such a concord’, Voetius would write (Disputationes Selectae, vol. 1, p. 306), ‘which subjects God to man, creator to creation.’

As a student Voetius chose Gomarus’s side, and he will have recognized in his professor a similar taste for scholarly and intellectual refinement and a sense of doctrinal precision that clashed head-on with the flexible positions of Bertius and Arminius. Voetius was a headstrong scholar even in his youth and we may well picture the intellectual tenacity with which he drove Professor Bertius so far that, in 1609, the latter called for his expulsion from the State College on unspecified charges of arrogance, condescension, and mockery. Voetius probably continued his Leiden studies outside the State College. For the time being, however, the political situation remained pro-Arminian. When Conrad Vorstius (1596–1622) was called to succeed the deceased Arminius in 1610, Gomarus thought it wiser to leave Leiden and go to Middelburg. Voetius, having finished his studies, also left the university and became a minister in Vlijmen, close to his home town. Towards the end of his period in Leiden, he had begun teaching logic, a position in which he tutored his young friend Franco Burgersdijk, the later Leiden philosopher and prototypical scholastic authority in England and America for two centuries to come.

On 5 May 1612, Voetius married Deliana van Diest (1591–1679), with whom he had ten children, seven of whom lived to adulthood, although Voetius outlived most of them, including his later Utrecht colleagues Paul and Daniël Voet. Preaching at Vlijmen, Voetius was soon to represent the Heusden ‘ring’ of local congregations within the classis of Gorinchem. Still a young man of twenty-nine, it was as a representative of this regional council that he attended the national synod at Dordrecht in November 1619. As expected, this convention outlawed Arminianism. Voetius had a very personal experience of the conflict between Remonstrants and Contra-Remonstrants. In his home town of Heusden, the Arminian party had tried for years to prevent his nomination as a minister. As was the case with other towns and villages, Arminian and Gomarist parties pleaded with the States and with Prince Maurice respectively, and committees were sent back from The Hague in an attempt at pacification. In Voetius’s case, it was Hugo Grotius who more than once intervened in the conflict with Voetius’s Remonstrant colleague Johannes de Greeff. When the Contra-Remonstrants won their fight with the support of Maurice in 1619, Voetius was happy to invite his former Leiden soul-mate Johannes Cloppenburgh (1592–1652) to join him as his colleague. In the summer of 1620, he again met many of his former professors, fellow students and colleagues, including his enemies Bertius and De Greeff, at the provincial synod in Leiden. Now, however, Voetius acted on behalf of the victorious party that purged the Church and the university. De Greeff was banished and ended up in Germany, Bertius went to Paris and became a Catholic.

Voetius had meanwhile continued his studies of logic and taught himself Arabic. Other academic work in the years leading up to his appointment as professor in the newly founded academy at Utrecht (see University of Utrecht) includes a variety of polemics against the enemies of the Reformed creed. Voetius continued to fight Arminianism and wrote against Socinianism as well, arguing that the rationalistic tendencies of both were entirely at odds with revealed Christian truth. He also engaged in a polemic with Cornelius Jansen (1585–1638), the later founder of Jansenism who was at the time professor of theology in Louvain, on the question of the legitimacy of a Protestant mission in conquered Catholic lands. Having proven his writing capabilities, and always showing a vast knowledge of both contemporary discussions and ancient philosophical and theological sources, Voetius was asked to become professor of theology, Hebrew and oriental languages at the new Illustrious School of Utrecht in June 1634. When the school was turned into a full university on 16 March 1636, he held a Sermon on the Usefulness of Academies and Schools on the Sunday preceding the occasion. Preaching would remain one of Voetius’s main occupations. In 1637, he accepted the position of part-time minister of the Utrecht church, a job which in practice amounted to a full-time extra burden, but which he continued for another thirty-six years.

In his double function of professor and minister, Voetius, with the support of his colleagues Meinardus Schotanus (1593–1644) and Carolus de Maets (1597–1651) and his later ‘Voetian’ school of junior theologians Gualterus de Bruyn (1618–53), Johannes Hoornbeek (1617–66), Andreas Essenius (1618–77) and Matthias Nethenus (1618–86), exerted a lasting influence not only on everyday life in Utrecht, but on Dutch culture at large. Inspired by Puritan models current in contemporary England, the country that he visited with his son Paul in 1636, the Utrecht theologian became the leading academic to support the ‘Further Reformation’. This movement within the Dutch Reformed Church called for a Christian purification of society through the private and public practice of piety. Speaking out against pawnbrokers, dancing, and ‘unnatural’ hair styles, and in favour of the strict observation of the Sabbath, Voetius and his colleagues fought any social custom which they thought might encourage man’s inborn inclination to sin. They never gained all-out support, however. Opposition to ‘backward Utrecht’ or Africa Ultrajectina was strong even amongst fellow Calvinists in the Dutch Republic, and most notably among the followers of the Leiden school of Abraham Heidanus and Johannes Cocceius. Opposition to Voetius in Utrecht itself also grew over the years and would eventually weaken, although never completely paralyse, Voetius’s moral authority. When, in 1660, the city government met with opposition to their decision to place ‘political commissioners’ in the church consistory, the Provincial States called in soldiers from neighbouring Holland and deposed two of Voetius’s most offensive colleagues. Since their criticism had been aimed at the personal gain received by provincial beneficiaries from canonical goods, a question on which Voetius had for many years expressed himself in the same vein, Utrecht’s theologus primarius was certainly implicated in this public manoeuvre against the growing power of the local clergy. With the further deposition of Nethenus in 1662 and the appointment of Frans Burman I in 1662 and Lodewijk Wolzogen in 1664, the city government deliberately introduced representatives of the modern, pro-Cartesian school of theologians into Utrecht’s university and church.

Nevertheless, Voetius continued to play an important role within both the university and the church. He was, as an old man, the first to resume Protestant services in the Utrecht Dom on 16 November 1673, three days after the withdrawal of French troops which had kept the city occupied for more than a year. Only a week later, seized with the cold, the eighty-four-year-old fell unconscious in the pulpit of the Catherijnekerk. This marked the end of his ministry, but Voetius kept his position at the university, acting as Rector as late as 1675–6. He died on 1 November 1676 and was buried two days later in the Catherijnekerk, which, of all the places of worship in The Netherlands, would one day be turned into the nation’s principal Catholic cathedral.

In his 1636 Sermon Voetius argued that all academic learning should be motivated solely by an admiration for the works of the Almighty and by the aim to explain the meaning of His Word. Moreover, no limits were to be set to the intellectual effort with which these aims might be attained. True to his own ideal, Voetius spent a lifetime devouring an incredible amount of literature, which he subsequently paraphrased and explained to his students. His strong belief in the need for thorough logical and philological training resulted in a massive production of university disputations; but it also sharpened the philosophical conflict that emerged between him and Descartes in the early 1640s, and which has become known as the ‘Utrecht Crisis’.

A correspondent and admirer of Descartes, the Utrecht professor of medicine and botany Henricus Regius had started to arouse the suspicion of his more conservative colleagues by openly criticizing the notion of ‘occult qualities’ on the occasion of the graduation of Florentius Schuyl in 1639 – and by publicly defending the theory of blood circulation in 1640. But it was on 8 December 1641 that, according to his colleagues, Regius went too far by having a student defend the thesis that man is an ens per accidens, i.e. not a single unity, but a composite of body and mind. The meeting disrupted into violence and Voetius, who was Rector of the university at the time, was asked to give a reaction that might ‘temper students in their reckless desire to discuss certain questions which threatened to draw them away from the study of theology’ (Testimonium, p. 25; Verbeek, La querelle d’Utrecht, p. 96). The theologian willingly obliged and wrote a set of theses On the Natures and Substantial Forms of Things which, on 23 and 24 December 1641, were publicly defended by his student Lambertus van den Waterlaet. Trying to safeguard both Scripture and the concepts and categories of scholastic physics against the supposed onslaught brought about by Copernicanism, the revival of atomism, and Descartes’s ‘new philosophy’, Voetius took the opportunity to criticize Descartes’s fanciful hypotheses in physics as well as his presumptuous intention to personally rewrite philosophy. Ominously, Voetius also argued that the new metaphysics of mind and body could lead to atheism.

Acting as a prompter to Regius, who published a Responsio to Voetius’s theses in February 1642, Descartes himself got fully involved in the matter when he rebutted Voetius’s arguments, saying that the danger of atheism was rather to be found in the Aristotelian philosophy of substantial forms. At a Sunday dinner party organized for the Groningen professor of philosophy Martin Schoock in July 1642, Voetius subsequently lured this former student into writing a book against Descartes, the infamous Admiranda Methodus Philosophiae Renati des Cartes (1643). Alarmed by reading some of its proofs and thinking they were by Voetius, Descartes aggravated things by publishing a Letter to Voetius, in which, just as he had done in his Letter to Father Dinet, he depicts the Utrecht theologian as a political troublemaker and an academic nitwit. The result, however, was that Descartes lost the support of his friends within the Utrecht city council. In an initial attempt at pacification, the magistrates had already banned the new philosophy from Utrecht University on 24 March 1642. Now they even summoned Descartes to appear before them (23 September 1643). Descartes never went, but years of ongoing lawsuits in Utrecht and in Groningen were to follow.

Voetius had already developed a dislike of Descartes in the late 1630s. Having read the Discours de la méthode, and not knowing about Descartes’s good relationship with Father Marin Mersenne (1588–1648), he had urged the latter to write against this much-admired founder of a ‘new sect’, whom some revered as a ‘God fallen from heaven’ (Mersenne, Correspondance, vol. 10, p. 164). Voetius was not free of the dishonesty and abuse that generally characterized the Utrecht Crisis. He may later have regretted his interference with the text of Schoock’s Admiranda Methodus, which had prompted Descartes to write his Epistola ad Voetium in the first place. Yet despite the slander from both sides, the documents relating to the Querelle d’Utrecht do give us an idea of the issues involved. Part of the conflict was of a methodological and didactical nature. Descartes repudiated Voetius’s ‘childish dialectics’ and argued that collecting a huge number of concepts, quotations, arguments, and distinctions from a variety of textbooks was a sterile and unworthy way of doing science. In the preface to the first volume of his Selected Disputations of 1648, Voetius defended himself by arguing that the way in which he introduced his students to the loci communes of Reformed theology was in line with current practice and that, in discussing matters of theology, his habit of referring to the testimony of others was wholly appropriate. Voetius did, in other words, what he was supposed to do in order to prepare his students for the ministry. In the same preface, Voetius took care to add some extra pastoral advice, issuing a new warning against Descartes, this ‘famous pupil of the Jesuits’ who had come to The Netherlands only to misuse its political laxness. He now added a long list of questions to ‘the Cartesians’, aimed at pointing out the inability of Cartesian philosophy to come to terms with a number of central issues in theology.

This had already been an important argument in the first stage of the Utrecht Crisis in 1641: inexperienced youngsters might draw ‘false and absurd’ conclusions from the new philosophy that were harmful to other disciplines, orthodox theology in particular (Testimonium, p. 66; Verbeek, La querelle d’Utrecht, p. 122). Since the proper function of philosophical theory was to provide the basic apparatus for the higher faculties, the introduction of alternative explanations in natural philosophy would seriously hamper students in furthering their studies. Reading Voetius’s pedagogical forewarnings, one should keep in mind that his systematization of Protestant dogma in Aristotelian terms was still in the process of being carried out. According to Voetius, the successful defense of Protestant thought against the repeated assaults by Catholics, Socinians and Arminians required precisely the type of scholastic treatment of questions of theology that we find in his seemingly aimless, but in fact highly structured, series of university disputations.

Descartes’s intention was to free philosophy from its literary tradition. This alone would have been enough to alarm Voetius. Yet below the surface of their methodological controversy lay a deeper philosophical divide. Cartesianism showed no signs of sensitivity to problems of theology. At the same time, it proved to be of great consequence for traditional philosophical questions such as those of substance and accident, substantial and accidental union, the unity of body and soul, the causal efficacy of material properties, etc. According to Voetius, however, these were also of utmost importance to theology and should therefore not be treated lightly in medicine (Regius’s field) or philosophy. In his 1641 theses On the Natures and Substantial Forms of Things, Voetius put out the warning that the acceptance of Descartes’s philosophy would cause the collapse of the scholastic metaphysics of substance. Indeed, in the Cartesian universe the whole metaphysical foundation of the concept of individuality would be lost. History would prove Voetius right. Within an extremely short period of time, the idea that natural philosophy could do without the substance–accident distinction became almost universally accepted. Leibniz’s monadology was a singular attempt to undo the metaphysical iconoclasm that Voetius had foreseen.

Also, not unlike Pascal, Voetius feared that Cartesian physics would ultimately dethrone God. Although his knowledge of Cartesian physics can only have been marginal in 1641, and although Voetius sufficiently relied on Aristotle’s refutation of ancient materialists not to be very much impressed by the rise of this ‘new philosophy’, he was well aware of the fact that the acceptance of mechanicism would break all ties between physics and theology. Encompassing the ideas of final causality and divine assistance, the scholastic tradition had provided a single body of scientific discourse. It made no distinction between the causal efficacy of formal, spiritual, or divine agents, nor between the ways in which these act upon and influence mental and physical events. Thus, natural philosophy and ethics, the mental and the physical, movement and growth, human behaviour and divine providence all fitted into a single body of scientific enquiry in which God could rule man in much the same way as the winds might rule the waves. There was only a conceptual dividing line between the ‘natural’ and ‘supernatural’ (Israel, Radical Enlightenment, p. 17).

The idea that nothing was to be gained from these new intellectual adventures also fuelled Voetius’s rejection of Cocceius’s interpretation of the Covenant. Contrary to Descartes, Cocceius had humanistic interests and hardly concerned himself with questions of philosophy. Yet like Descartes, he triggered Voetius’s alarm by abandoning the apologetic framework of scholastic logic and argumentation. Cocceius’s innovative reading of the Scriptures contrasts with Voetius’s complicated explanations of the way in which God distributes inner and outer grace just as much as Descartes’s graphic descriptions of the microscopic and macroscopic worlds contrast with Voetius’s stubborn rejection of the Copernican hypo-thesis. And yet Voetius struck a chord with many of his contemporaries.

Although it was probably not Voetius himself, but a group of Leiden ministers and theologians who in 1656 fought Cartesianism and Cocceianism in a series of pamphlets under the name of Suetonius Tranquillus, Voetius was certainly their source of inspiration, just as he was regarded the prime enemy by his Leiden opponents – Heidanus in particular. Voetius also sparked a flood of anti-Copernican literature and thus succeeded in forming a ‘Voetian’ school that would oppose Cartesian philosophy for many decades and Cocceian theology for over a century.

To understand Voetianism is to take seriously its uniquely religious motivation. Voetius strongly believed in the defence of piety by scientific method. Yet he also believed that the accepted methods sufficed. Aristotelian philosophy had historically proved its worth; and for answering a variety of questions in theology, Aristotelian logic and metaphysics seemingly could not be done without. Besides being presumptuous, the Copernican, Cartesian, and Cocceian displays of intellectual audacity were, by contrast, intrinsically unsafe on account of their philosophical uncertainty. They could only lead to doubt and scepticism, and thus, ultimately, to loss of faith. The fact that Descartes even encouraged a ‘method’ of doubt had been one of the reasons for Voetius’s initial dislike of Cartesianism, as it would later be for other Calvinist scholastics like Jacobus Revius. Others might feel a similar sense of alarm. During the heydays of Cartesianism and Cocceianism in the late 1660s, even an arch-enemy of Voetius such as the Groningen theologian Samuel Maresius would be prepared to be reconciled with him.

Voetius’s project of building a Reformed scholastic theology led him to answer detailed questions of a practical nature as well. His Church Politics (Politica Ecclesiastica) discusses everything from church organization and ecclesiastical law to the fine points of Protestant ritual, the daily life of a minister and the appropriate Calvinist attitude towards other churches. Again, however, Voetius’s scholasticism backfired. In 1668, Lodovicus Molinaeus (or Louis Du Moulin, 1605–84) – an English Presbyterian and son of the famous French Protestant theologian and former Leiden professor of philosophy Petrus Molinaeus – published a small book entitled Papa Ultrajectinus, or The Utrecht Pope, in which Voetius’s dependence on Catholic sources was linked to a supposed ‘Papist’ strategy aimed at seeking power in both church and state. Reynier Vogelsangh, a Voetian theologian from Hertogenbosch, was quick to answer Molinaeus with a pamphlet in which he argued that in fact Voetius distinguished far better between the respective powers of church and state than Molinaeus himself. But the damage had already been done. Voetius’s nickname was too attractive not to stick, especially with those who bore a grudge against Utrecht’s powerful theologian.

Except for a small minority of admirers in orthodox circles, future centuries would abide by the hostile image of Voetius as a model of inflexibility and an archetypal Aristotelian diehard. Such an image tends to obscure Voetius’s unique position as a scholar who translated to a Calvinist public the vast Christian heritage of theological literature from the Church Fathers and the works of the great scholastics down to the Italian, Spanish and Portuguese recentiores. His rigid interpretation of Christian praecisitas has made him equally notorious. Calling for a strict observation of the Sabbath and clamouring against dancing, gambling and the theatre, Voetius indeed showed himself inflexible. As such, he may well have exerted a greater influence on Dutch culture than any other intellectual, including Erasmus and Spinoza. Yet Voetius was more than a weary and vexatious formalist. He was not only a devoted shepherd to his flock, but also an inspiration to generations of Utrecht students. As a skilled tutor and lifelong admirer of Thomas à Kempis, his ultimate aim was to inspire in his countrymen a Christian rebirth in practice and thought. To that end, he never hesitated to explain why the Calvinist position on grace was not one of fear and apathy, but of comfort and contentment, and to offer his fellow-citizens and students practical guidance in the exercise of prayer and contemplation. The fact that even contemporaries who did not share his views looked upon the Utrecht professor with considerable awe is best illustrated by the poem that Descartes’s friend Constantijn Huygens wrote on the occasion of Voetius’s death, and which ends with the lines: ‘Who would not, if it were possible, want to be a Descartes, a Cocceius or a Voetius?’.

Bibliography

Proeve van de Cracht der Godsalicheyt (Amsterdam, 1628).

Oratio de pietate cum scientia conjungenda (Utrecht, 1634).

Desperata causa Papatus, novissime prodita a Cornelio Jansenio (Amsterdam, 1635).

Thersites heautontimorumenos (Utrecht, 1635).

Sermoen van de nutticheydt der Academien ende Scholen, mitsgaders der wetenschappen ende consten die in de selve gheleert werden (Utrecht, 1636).

Excercitia et bibliotheca studiosi theologiae (Utrecht, 1644).

Een kort tractaetjen van de danssen, tot dienst van den eenvoudigen (Utrecht, 1644).

Selectarum Disputationum theologicarum, 5 vols (Utrecht, 1648; Amsterdam, 1667; Utrecht, 1669).

Theologisch advys over ’t gebruyck van kerckelijcke goederen. Eerste deel (Utrecht, 1653).

Wolcke der Getuygen, Ofte het Tweede Deel, van het Theologisch advys Over ’t gebruyck van Kerckelijcke goederen (Utrecht, 1656).

Politica ecclesiastica, 3 pts in 4 vols (Amsterdam, 1663–76).

Ta Askêtika sive Exercitia pietatis in usum juventutis academicae nunc edita (Gorinchem, 1664; critical edn by C.A. de Niet, Utrecht, 1996).

Selectarum Disputationum Fasciculus (Amsterdam, 1889).

Other Relevant Works

Bertius, Petrus, Aen-spraeck aen D. Fr. Gomarum op zijne bedenckinghe over de lijck-oratie ghedaen na de begraefnisse van Jacobus Arminius zaligher (Leiden, 1610).

Descartes, René, Oeuvres, 12 vols, ed. by Charles Adam and Paul Tannery (Paris, 1897–1913; Paris, 1964–71; Paris, 1996).

Huygens, Constantijn, De Gedichten van Constantijn Huygens, ed. by J. A. Worp, vol. 8 (Groningen, 1898), pp. 156–7.

Mersenne, Marin, Correspondance du P. Marin Mersenne: Religieux minime, ed. by Paul Tannery, Cornelis de Waard, Bernard Rochot, and René Pintard (Paris, 1945–72).

Molinaeus, Ludovicus, Papa Ultrajectinus: Seu Mysterium Iniquitatis reductum à Clarißimo Viro Gisberto Voetio in opere Politiae Ecclesiasticae (London, 1668).

Philalethius, Irenaeus, pseud. for Abraham Heidanus, Bedenkingen, Op den Staat des Geschils, Over de Cartesiaensche Philosophie, En op de Nader Openinghe Over eenige stucken de Theologie raeckende (Rotterdam, 1656).

Regius, Henricus, Responsio, sive Notae in Appendicem ad Colloraria Theologica-Philosophica … D. Gisberti Voetii (Utrecht, 1642).

Schoockius, Martinus, Admiranda Methodus Novae Philosophiae Renati des Cartes (Utrecht, 1643).

Tranquillus, Suetonius, Staat des Geschils, Over de Cartesiaensche Philosophie (Utrecht, 1656).

———, Nader Openinge, Van eenige stucken in de Cartesiaensche Philosophie Raeckende de H. Theologie (Leiden, 1656).

———, Den Overtuyghden Cartesiaen… (Leiden, 1656).

———, Verdedichde oprechticheyt van Suetonius Tranquillus gestelt tegen de Overtuyghde quaetwilligheyt van Irenaeus Philalethius (Leiden, 1656).

Testimonium Academiae Ultrajectinae, et Narratio Historica quà defensae, quà

exterminatae novae Philosophiae (Utrecht, 1643).

Voet, Paulus, Prima Philosophia Reformata (Utrecht, 1657).

Vogelsangh, Reynier, Breves ac succinctae ad Ludiomaei Colvini Papam Ultrajectinum Animadversiones (London [= Utrecht?], 1668).

Waterlaet, Lambertus van den, Diatribe theologica de jubileo ad jubileum Urbani VIII. promulgatum hoc anno MDCXLI (Utrecht, 1614).

Further Reading

Asselt, W.J. van and E. Dekker (eds), De scholastieke Voetius. Een luisteroefening aan de hand van Voetius’ Disputationes Selectae (Zoetermeer, 1995).

———, ‘G. Voetius, gereformeerd scholasticus’, in Aart de Groot and Otto J. de Jong (eds), Vier eeuwen theologie in Utrecht. Bijdragen tot de geschiedenis van de theologische faculteit aan de Universiteit Utrecht (Zoetermeer, 2001), pp. 99–108.

Bos, E.-J. (ed.), Verantwoordingh van Renatus Descartes aen d’Achtbare Overigheit van Uitrecht: Een onbekende Descartes-tekst (Amsterdam, 1996).

Bunge, Wiep van, From Stevin to Spinoza: An Essay on Philosophy in the Seventeenth-Century Dutch Republic (Leiden, 2001).

Duker, A.C., Gisbertus Voetius, 4 vols (Leiden, 1897–1915; repr. Leiden, 1989).

Groot, Aart de and Otto J. de Jong, Vier eeuwen theologie in Utrecht: Bijdragen tot de geschiedenis van de theologische faculteit aan de Universiteit Utrecht (Zoetermeer, 2001).

Israel, Jonathan I., Radical Enlightenment: Philosophy and the Making of Modernity 1650–1750 (Oxford, 2001).

Knipscheer, F.S., ‘Voetius (Gisbertus), in P.C. Molhuysen, P.J. Blok and F.K.H. Kossmann (eds), Nieuw Nederlandsch Biografisch Woordenboek, vol. 7 (Leiden, 1927), cols 1279–82.

Nauta, D., ‘Voetius, Gisbertus (Gijsbert Voet)’, Biografisch lexicon voor de geschiedenis van het Nederlandse Protestantisme, vol. 2 (Kampen, 1983), pp. 443–9.

Oort, J. van, C. Graafland, A. de Groot and O.J. de Jong (eds), De onbekende Voetius. Voordrachten wetenschappelijk symposium Utrecht 3 maart 1989 (Kampen, 1989).

Ruler, J. A. van, ‘New Philosophy to Old Standards: Voetius’s Vindication of Divine Concurrence and Secondary Causality’, in Nederlands Archief voor Kerkgeschiedenis / Dutch Review of Church History, vol. 71 (1991), pp. 58–91.

———, ‘Franco Petri Burgersdijk and the Case of Calvinism Within the Neo-Scholastic Tradition’, in E.P. Bos and H.A. Krop (eds), Franco Burgersdijk (1590–1635), Studies in the History of Ideas in the Low Countries (Amsterdam and Atlanta, GA, 1993), pp. 37–65.

———, The Crisis of Causality: Voetius and Descartes on God, Nature, and Change (Leiden, 1995)

———, ‘Waren er muilezels op de zesde dag? Descartes, Voetius en de zeventiende-eeuwse methodenstrijd’, in Florieke van Egmond, Eric Jorink and Rienk Vermij (eds), Kometen, monsters en muilezels. Het veranderende natuurbeeld en de natuurwetenschap in de zeventiende eeuw (Haarlem, 1999), pp. 120–32.

———, ‘ “Something, I know not what.” The Concept of Substance in Early Modern Thought’, in Lodi Nauta and Arjo Vanderjagt (eds), Between Imagination and Demonstration. Essays in the History of Science and Philosophy Presented to John D. North (Leiden, 1999), pp. 365–93.

Steenblok, C., Gisbertus Voetius: Zijn leven en werken (Rhenen, 1942; Gouda, 1976).

Verbeek, T. (ed.), La querelle d’Utrecht (Paris, 1988).

———, ‘Voetius en Descartes’, in J. van Oort, C. Graafland, A. de Groot and O.J. de Jong (eds), De onbekende Voetius. Voordrachten wetenschappelijk symposium Utrecht 3 maart 1989 (Kampen, 1989), pp. 200–219.

———, Descartes and the Dutch: Early Reactions to Cartesian Philosophy 1637–1650 (Carbondale and Edwardsville, IL, 1992).

———, ‘From “Learned Ignorance” to Scepticism; Descartes and Calvinist Orthodoxy’, in Richard H. Popkin and Arjo Vanderjagt (eds), Scepticism and Irreligion in the Seventeenth and Eighteenth Centuries (Leiden, 1993), pp. 31–45.

Vermij, Rienk, The Calvinist Copernicans: The reception of the new astronomy in the Dutch Republic, 1575–1750 (Amsterdam, 2002).

Han van Ruler

The Dictionary of Seventeenth and Eighteenth-Century Dutch Philosophers

2 volumes : ISBN 1 85506 966 0 © Thoemmes Continuum, 2003

Source: https://witsius.wordpress.com

Dutch Reformed theologian and first Protestant to write a comprehensive theology of mission

Voetius not only overlapped with Witsius for 40 odd years, but he was an important subject in the Dutch Reformed world in which Witsius lived and breathed. Not only was Witsius heavily influenced by Voetius, but Witsius’ own work was – in a sense – an attempt to reconcile the best of Voetius and Cocceius and their respective methodologies. Any careful study into Witsius must grapple with Gijsbert Voet, and hopefully the following biography presents a clear albeit brief look into this important Dutch father.

Biography of Voetius

Born in the small fortified city of Heusden as the son of Paulus Voet and Maria de Jongeling, Gisbertus (or Gijsbert) Voetius’s early years were dominated by the experience of war. Heusden was on the front line in both a military and a religious sense, as it was situated on the southern bank of the river Meuse that would later form the borderline dividing Catholic and Protestant parts of the country. Voetius’s relatives were directly involved in the conflict with Spain. Grandfather Nicolaas Dirkszoon Voet, heir to a Westphalian noble family, died in prison in ’s Hertogenbosch where he was kept on account of his support of William the Silent. Several members of Gijsbert’s mother’s family would flee the city, leaving all their possessions behind in order to accompany the Prince of Orange to Breda. Voetius’s father meanwhile saw his own property being demolished in the rampage around Heusden. Having joined the State militias for a second time in 1592, he was killed in the siege of Bredevoort in 1597, leaving behind the sickly Maria with four children.

Gijsbert was then only eight and went to live with the local blacksmith, expenses being defrayed by the city government. Noticing his excellence in the study of letters, the Heusden magistrates decided to prolong their sustenance. In 1604 they sent their youngster – of small stature, but intellectually mature – as ‘the city’s student’ to the Leiden State College. Voetius seems to have felt at home there. The daily readings of the Scriptures and the Heidelberg Catechism as well as the College’s propaedeutic courses in philosophy doubtlessly contributed to his later belief in the importance of a well-defined body of student material, such as it appears in his Exercitia et bibliotheca studiosi theologiae of 1644. In philosophy, Voetius showed a special predilection for the works of Bartholomaeus Keckermann (1571–1609), but his philosophical schooling was far from one-sided. Together with fellow students such as Simon Episcopius and Caspar Barlaeus, both of whom, like his professor in logic Petrus Bertius, would later become champions of the Arminian cause, Voetius read a huge amount of ancient literature. He studied Lucretius’s De rerum natura alongside Aristotelian, Stoic and neo-Stoic classics of physics, ethics and psychology, and also read more recent works on medicine, natural history and geography. He further exercised his mathematical skills, attended chemical and anatomical experiments, and is said to have learned to play the zither, the organ and the flute.

Yet of most concern to anyone attending Leiden courses in theology during these years was the question of Calvinist dogmatics and its foundation in neo-scholastic metaphysics. The question of divine grace and human freedom divided the followers of Jacobus Arminius and Franciscus Gomarus and called for a close reading of the relevant philosophical background. Treating philosophical questions with the help of Iberian commentaries on Aristotle, Voetius’s professor of philosophy Gilbertus Jacchaeus had been warned in 1607 to abstain from dealing with theological questions. This did not mean that Catholic philosophers would become less thoroughly read. Indeed, as Bertius reproached Franciscus Gomarus in 1610: ‘Who is it, then, that every day still cites Durandus, Gabriel Biel, Molina, Bonaventura, Cumelus, Dominicus Bañez, C. Javellus, Gregory of Valentia, and others besides these?’ (Aen-spraeck, p. 26.) Bertius’s list indicates that the Leiden battle over the question of freedom and grace was fought along the same lines as that which had divided Jesuits and Dominicans during the controversies De Auxiliis within the Roman Catholic Church. Quoting Catholic authors was an accepted strategy in both the Arminian and the Gomarist camps. Many years later, Gisbertus’s eldest son, the philosopher-lawyer Paul Voet, would continue to praise the Dominicans for their ‘safe way’ in theology against the ‘common’ Jesuit enemy (Prima Philosophia Reformata, p. 2). Indeed, both Calvinists and Dominicans regarded the Jesuit search for a concordia between divine grace and human will as a shaky compromise prompted by an intellectual lack of nerve: ‘We do not go for such a concord’, Voetius would write (Disputationes Selectae, vol. 1, p. 306), ‘which subjects God to man, creator to creation.’

As a student Voetius chose Gomarus’s side, and he will have recognized in his professor a similar taste for scholarly and intellectual refinement and a sense of doctrinal precision that clashed head-on with the flexible positions of Bertius and Arminius. Voetius was a headstrong scholar even in his youth and we may well picture the intellectual tenacity with which he drove Professor Bertius so far that, in 1609, the latter called for his expulsion from the State College on unspecified charges of arrogance, condescension, and mockery. Voetius probably continued his Leiden studies outside the State College. For the time being, however, the political situation remained pro-Arminian. When Conrad Vorstius (1596–1622) was called to succeed the deceased Arminius in 1610, Gomarus thought it wiser to leave Leiden and go to Middelburg. Voetius, having finished his studies, also left the university and became a minister in Vlijmen, close to his home town. Towards the end of his period in Leiden, he had begun teaching logic, a position in which he tutored his young friend Franco Burgersdijk, the later Leiden philosopher and prototypical scholastic authority in England and America for two centuries to come.

On 5 May 1612, Voetius married Deliana van Diest (1591–1679), with whom he had ten children, seven of whom lived to adulthood, although Voetius outlived most of them, including his later Utrecht colleagues Paul and Daniël Voet. Preaching at Vlijmen, Voetius was soon to represent the Heusden ‘ring’ of local congregations within the classis of Gorinchem. Still a young man of twenty-nine, it was as a representative of this regional council that he attended the national synod at Dordrecht in November 1619. As expected, this convention outlawed Arminianism. Voetius had a very personal experience of the conflict between Remonstrants and Contra-Remonstrants. In his home town of Heusden, the Arminian party had tried for years to prevent his nomination as a minister. As was the case with other towns and villages, Arminian and Gomarist parties pleaded with the States and with Prince Maurice respectively, and committees were sent back from The Hague in an attempt at pacification. In Voetius’s case, it was Hugo Grotius who more than once intervened in the conflict with Voetius’s Remonstrant colleague Johannes de Greeff. When the Contra-Remonstrants won their fight with the support of Maurice in 1619, Voetius was happy to invite his former Leiden soul-mate Johannes Cloppenburgh (1592–1652) to join him as his colleague. In the summer of 1620, he again met many of his former professors, fellow students and colleagues, including his enemies Bertius and De Greeff, at the provincial synod in Leiden. Now, however, Voetius acted on behalf of the victorious party that purged the Church and the university. De Greeff was banished and ended up in Germany, Bertius went to Paris and became a Catholic.

Voetius had meanwhile continued his studies of logic and taught himself Arabic. Other academic work in the years leading up to his appointment as professor in the newly founded academy at Utrecht (see University of Utrecht) includes a variety of polemics against the enemies of the Reformed creed. Voetius continued to fight Arminianism and wrote against Socinianism as well, arguing that the rationalistic tendencies of both were entirely at odds with revealed Christian truth. He also engaged in a polemic with Cornelius Jansen (1585–1638), the later founder of Jansenism who was at the time professor of theology in Louvain, on the question of the legitimacy of a Protestant mission in conquered Catholic lands. Having proven his writing capabilities, and always showing a vast knowledge of both contemporary discussions and ancient philosophical and theological sources, Voetius was asked to become professor of theology, Hebrew and oriental languages at the new Illustrious School of Utrecht in June 1634. When the school was turned into a full university on 16 March 1636, he held a Sermon on the Usefulness of Academies and Schools on the Sunday preceding the occasion. Preaching would remain one of Voetius’s main occupations. In 1637, he accepted the position of part-time minister of the Utrecht church, a job which in practice amounted to a full-time extra burden, but which he continued for another thirty-six years.

In his double function of professor and minister, Voetius, with the support of his colleagues Meinardus Schotanus (1593–1644) and Carolus de Maets (1597–1651) and his later ‘Voetian’ school of junior theologians Gualterus de Bruyn (1618–53), Johannes Hoornbeek (1617–66), Andreas Essenius (1618–77) and Matthias Nethenus (1618–86), exerted a lasting influence not only on everyday life in Utrecht, but on Dutch culture at large. Inspired by Puritan models current in contemporary England, the country that he visited with his son Paul in 1636, the Utrecht theologian became the leading academic to support the ‘Further Reformation’. This movement within the Dutch Reformed Church called for a Christian purification of society through the private and public practice of piety. Speaking out against pawnbrokers, dancing, and ‘unnatural’ hair styles, and in favour of the strict observation of the Sabbath, Voetius and his colleagues fought any social custom which they thought might encourage man’s inborn inclination to sin. They never gained all-out support, however. Opposition to ‘backward Utrecht’ or Africa Ultrajectina was strong even amongst fellow Calvinists in the Dutch Republic, and most notably among the followers of the Leiden school of Abraham Heidanus and Johannes Cocceius. Opposition to Voetius in Utrecht itself also grew over the years and would eventually weaken, although never completely paralyse, Voetius’s moral authority. When, in 1660, the city government met with opposition to their decision to place ‘political commissioners’ in the church consistory, the Provincial States called in soldiers from neighbouring Holland and deposed two of Voetius’s most offensive colleagues. Since their criticism had been aimed at the personal gain received by provincial beneficiaries from canonical goods, a question on which Voetius had for many years expressed himself in the same vein, Utrecht’s theologus primarius was certainly implicated in this public manoeuvre against the growing power of the local clergy. With the further deposition of Nethenus in 1662 and the appointment of Frans Burman I in 1662 and Lodewijk Wolzogen in 1664, the city government deliberately introduced representatives of the modern, pro-Cartesian school of theologians into Utrecht’s university and church.

Nevertheless, Voetius continued to play an important role within both the university and the church. He was, as an old man, the first to resume Protestant services in the Utrecht Dom on 16 November 1673, three days after the withdrawal of French troops which had kept the city occupied for more than a year. Only a week later, seized with the cold, the eighty-four-year-old fell unconscious in the pulpit of the Catherijnekerk. This marked the end of his ministry, but Voetius kept his position at the university, acting as Rector as late as 1675–6. He died on 1 November 1676 and was buried two days later in the Catherijnekerk, which, of all the places of worship in The Netherlands, would one day be turned into the nation’s principal Catholic cathedral.

In his 1636 Sermon Voetius argued that all academic learning should be motivated solely by an admiration for the works of the Almighty and by the aim to explain the meaning of His Word. Moreover, no limits were to be set to the intellectual effort with which these aims might be attained. True to his own ideal, Voetius spent a lifetime devouring an incredible amount of literature, which he subsequently paraphrased and explained to his students. His strong belief in the need for thorough logical and philological training resulted in a massive production of university disputations; but it also sharpened the philosophical conflict that emerged between him and Descartes in the early 1640s, and which has become known as the ‘Utrecht Crisis’.

A correspondent and admirer of Descartes, the Utrecht professor of medicine and botany Henricus Regius had started to arouse the suspicion of his more conservative colleagues by openly criticizing the notion of ‘occult qualities’ on the occasion of the graduation of Florentius Schuyl in 1639 – and by publicly defending the theory of blood circulation in 1640. But it was on 8 December 1641 that, according to his colleagues, Regius went too far by having a student defend the thesis that man is an ens per accidens, i.e. not a single unity, but a composite of body and mind. The meeting disrupted into violence and Voetius, who was Rector of the university at the time, was asked to give a reaction that might ‘temper students in their reckless desire to discuss certain questions which threatened to draw them away from the study of theology’ (Testimonium, p. 25; Verbeek, La querelle d’Utrecht, p. 96). The theologian willingly obliged and wrote a set of theses On the Natures and Substantial Forms of Things which, on 23 and 24 December 1641, were publicly defended by his student Lambertus van den Waterlaet. Trying to safeguard both Scripture and the concepts and categories of scholastic physics against the supposed onslaught brought about by Copernicanism, the revival of atomism, and Descartes’s ‘new philosophy’, Voetius took the opportunity to criticize Descartes’s fanciful hypotheses in physics as well as his presumptuous intention to personally rewrite philosophy. Ominously, Voetius also argued that the new metaphysics of mind and body could lead to atheism.

Acting as a prompter to Regius, who published a Responsio to Voetius’s theses in February 1642, Descartes himself got fully involved in the matter when he rebutted Voetius’s arguments, saying that the danger of atheism was rather to be found in the Aristotelian philosophy of substantial forms. At a Sunday dinner party organized for the Groningen professor of philosophy Martin Schoock in July 1642, Voetius subsequently lured this former student into writing a book against Descartes, the infamous Admiranda Methodus Philosophiae Renati des Cartes (1643). Alarmed by reading some of its proofs and thinking they were by Voetius, Descartes aggravated things by publishing a Letter to Voetius, in which, just as he had done in his Letter to Father Dinet, he depicts the Utrecht theologian as a political troublemaker and an academic nitwit. The result, however, was that Descartes lost the support of his friends within the Utrecht city council. In an initial attempt at pacification, the magistrates had already banned the new philosophy from Utrecht University on 24 March 1642. Now they even summoned Descartes to appear before them (23 September 1643). Descartes never went, but years of ongoing lawsuits in Utrecht and in Groningen were to follow.

Voetius had already developed a dislike of Descartes in the late 1630s. Having read the Discours de la méthode, and not knowing about Descartes’s good relationship with Father Marin Mersenne (1588–1648), he had urged the latter to write against this much-admired founder of a ‘new sect’, whom some revered as a ‘God fallen from heaven’ (Mersenne, Correspondance, vol. 10, p. 164). Voetius was not free of the dishonesty and abuse that generally characterized the Utrecht Crisis. He may later have regretted his interference with the text of Schoock’s Admiranda Methodus, which had prompted Descartes to write his Epistola ad Voetium in the first place. Yet despite the slander from both sides, the documents relating to the Querelle d’Utrecht do give us an idea of the issues involved. Part of the conflict was of a methodological and didactical nature. Descartes repudiated Voetius’s ‘childish dialectics’ and argued that collecting a huge number of concepts, quotations, arguments, and distinctions from a variety of textbooks was a sterile and unworthy way of doing science. In the preface to the first volume of his Selected Disputations of 1648, Voetius defended himself by arguing that the way in which he introduced his students to the loci communes of Reformed theology was in line with current practice and that, in discussing matters of theology, his habit of referring to the testimony of others was wholly appropriate. Voetius did, in other words, what he was supposed to do in order to prepare his students for the ministry. In the same preface, Voetius took care to add some extra pastoral advice, issuing a new warning against Descartes, this ‘famous pupil of the Jesuits’ who had come to The Netherlands only to misuse its political laxness. He now added a long list of questions to ‘the Cartesians’, aimed at pointing out the inability of Cartesian philosophy to come to terms with a number of central issues in theology.

This had already been an important argument in the first stage of the Utrecht Crisis in 1641: inexperienced youngsters might draw ‘false and absurd’ conclusions from the new philosophy that were harmful to other disciplines, orthodox theology in particular (Testimonium, p. 66; Verbeek, La querelle d’Utrecht, p. 122). Since the proper function of philosophical theory was to provide the basic apparatus for the higher faculties, the introduction of alternative explanations in natural philosophy would seriously hamper students in furthering their studies. Reading Voetius’s pedagogical forewarnings, one should keep in mind that his systematization of Protestant dogma in Aristotelian terms was still in the process of being carried out. According to Voetius, the successful defense of Protestant thought against the repeated assaults by Catholics, Socinians and Arminians required precisely the type of scholastic treatment of questions of theology that we find in his seemingly aimless, but in fact highly structured, series of university disputations.

Descartes’s intention was to free philosophy from its literary tradition. This alone would have been enough to alarm Voetius. Yet below the surface of their methodological controversy lay a deeper philosophical divide. Cartesianism showed no signs of sensitivity to problems of theology. At the same time, it proved to be of great consequence for traditional philosophical questions such as those of substance and accident, substantial and accidental union, the unity of body and soul, the causal efficacy of material properties, etc. According to Voetius, however, these were also of utmost importance to theology and should therefore not be treated lightly in medicine (Regius’s field) or philosophy. In his 1641 theses On the Natures and Substantial Forms of Things, Voetius put out the warning that the acceptance of Descartes’s philosophy would cause the collapse of the scholastic metaphysics of substance. Indeed, in the Cartesian universe the whole metaphysical foundation of the concept of individuality would be lost. History would prove Voetius right. Within an extremely short period of time, the idea that natural philosophy could do without the substance–accident distinction became almost universally accepted. Leibniz’s monadology was a singular attempt to undo the metaphysical iconoclasm that Voetius had foreseen.

Also, not unlike Pascal, Voetius feared that Cartesian physics would ultimately dethrone God. Although his knowledge of Cartesian physics can only have been marginal in 1641, and although Voetius sufficiently relied on Aristotle’s refutation of ancient materialists not to be very much impressed by the rise of this ‘new philosophy’, he was well aware of the fact that the acceptance of mechanicism would break all ties between physics and theology. Encompassing the ideas of final causality and divine assistance, the scholastic tradition had provided a single body of scientific discourse. It made no distinction between the causal efficacy of formal, spiritual, or divine agents, nor between the ways in which these act upon and influence mental and physical events. Thus, natural philosophy and ethics, the mental and the physical, movement and growth, human behaviour and divine providence all fitted into a single body of scientific enquiry in which God could rule man in much the same way as the winds might rule the waves. There was only a conceptual dividing line between the ‘natural’ and ‘supernatural’ (Israel, Radical Enlightenment, p. 17).

The idea that nothing was to be gained from these new intellectual adventures also fuelled Voetius’s rejection of Cocceius’s interpretation of the Covenant. Contrary to Descartes, Cocceius had humanistic interests and hardly concerned himself with questions of philosophy. Yet like Descartes, he triggered Voetius’s alarm by abandoning the apologetic framework of scholastic logic and argumentation. Cocceius’s innovative reading of the Scriptures contrasts with Voetius’s complicated explanations of the way in which God distributes inner and outer grace just as much as Descartes’s graphic descriptions of the microscopic and macroscopic worlds contrast with Voetius’s stubborn rejection of the Copernican hypo-thesis. And yet Voetius struck a chord with many of his contemporaries.

Although it was probably not Voetius himself, but a group of Leiden ministers and theologians who in 1656 fought Cartesianism and Cocceianism in a series of pamphlets under the name of Suetonius Tranquillus, Voetius was certainly their source of inspiration, just as he was regarded the prime enemy by his Leiden opponents – Heidanus in particular. Voetius also sparked a flood of anti-Copernican literature and thus succeeded in forming a ‘Voetian’ school that would oppose Cartesian philosophy for many decades and Cocceian theology for over a century.

To understand Voetianism is to take seriously its uniquely religious motivation. Voetius strongly believed in the defence of piety by scientific method. Yet he also believed that the accepted methods sufficed. Aristotelian philosophy had historically proved its worth; and for answering a variety of questions in theology, Aristotelian logic and metaphysics seemingly could not be done without. Besides being presumptuous, the Copernican, Cartesian, and Cocceian displays of intellectual audacity were, by contrast, intrinsically unsafe on account of their philosophical uncertainty. They could only lead to doubt and scepticism, and thus, ultimately, to loss of faith. The fact that Descartes even encouraged a ‘method’ of doubt had been one of the reasons for Voetius’s initial dislike of Cartesianism, as it would later be for other Calvinist scholastics like Jacobus Revius. Others might feel a similar sense of alarm. During the heydays of Cartesianism and Cocceianism in the late 1660s, even an arch-enemy of Voetius such as the Groningen theologian Samuel Maresius would be prepared to be reconciled with him.

Voetius’s project of building a Reformed scholastic theology led him to answer detailed questions of a practical nature as well. His Church Politics (Politica Ecclesiastica) discusses everything from church organization and ecclesiastical law to the fine points of Protestant ritual, the daily life of a minister and the appropriate Calvinist attitude towards other churches. Again, however, Voetius’s scholasticism backfired. In 1668, Lodovicus Molinaeus (or Louis Du Moulin, 1605–84) – an English Presbyterian and son of the famous French Protestant theologian and former Leiden professor of philosophy Petrus Molinaeus – published a small book entitled Papa Ultrajectinus, or The Utrecht Pope, in which Voetius’s dependence on Catholic sources was linked to a supposed ‘Papist’ strategy aimed at seeking power in both church and state. Reynier Vogelsangh, a Voetian theologian from Hertogenbosch, was quick to answer Molinaeus with a pamphlet in which he argued that in fact Voetius distinguished far better between the respective powers of church and state than Molinaeus himself. But the damage had already been done. Voetius’s nickname was too attractive not to stick, especially with those who bore a grudge against Utrecht’s powerful theologian.

Except for a small minority of admirers in orthodox circles, future centuries would abide by the hostile image of Voetius as a model of inflexibility and an archetypal Aristotelian diehard. Such an image tends to obscure Voetius’s unique position as a scholar who translated to a Calvinist public the vast Christian heritage of theological literature from the Church Fathers and the works of the great scholastics down to the Italian, Spanish and Portuguese recentiores. His rigid interpretation of Christian praecisitas has made him equally notorious. Calling for a strict observation of the Sabbath and clamouring against dancing, gambling and the theatre, Voetius indeed showed himself inflexible. As such, he may well have exerted a greater influence on Dutch culture than any other intellectual, including Erasmus and Spinoza. Yet Voetius was more than a weary and vexatious formalist. He was not only a devoted shepherd to his flock, but also an inspiration to generations of Utrecht students. As a skilled tutor and lifelong admirer of Thomas à Kempis, his ultimate aim was to inspire in his countrymen a Christian rebirth in practice and thought. To that end, he never hesitated to explain why the Calvinist position on grace was not one of fear and apathy, but of comfort and contentment, and to offer his fellow-citizens and students practical guidance in the exercise of prayer and contemplation. The fact that even contemporaries who did not share his views looked upon the Utrecht professor with considerable awe is best illustrated by the poem that Descartes’s friend Constantijn Huygens wrote on the occasion of Voetius’s death, and which ends with the lines: ‘Who would not, if it were possible, want to be a Descartes, a Cocceius or a Voetius?’.

Bibliography

Proeve van de Cracht der Godsalicheyt (Amsterdam, 1628).

Oratio de pietate cum scientia conjungenda (Utrecht, 1634).

Desperata causa Papatus, novissime prodita a Cornelio Jansenio (Amsterdam, 1635).

Thersites heautontimorumenos (Utrecht, 1635).

Sermoen van de nutticheydt der Academien ende Scholen, mitsgaders der wetenschappen ende consten die in de selve gheleert werden (Utrecht, 1636).

Excercitia et bibliotheca studiosi theologiae (Utrecht, 1644).

Een kort tractaetjen van de danssen, tot dienst van den eenvoudigen (Utrecht, 1644).

Selectarum Disputationum theologicarum, 5 vols (Utrecht, 1648; Amsterdam, 1667; Utrecht, 1669).

Theologisch advys over ’t gebruyck van kerckelijcke goederen. Eerste deel (Utrecht, 1653).

Wolcke der Getuygen, Ofte het Tweede Deel, van het Theologisch advys Over ’t gebruyck van Kerckelijcke goederen (Utrecht, 1656).

Politica ecclesiastica, 3 pts in 4 vols (Amsterdam, 1663–76).

Ta Askêtika sive Exercitia pietatis in usum juventutis academicae nunc edita (Gorinchem, 1664; critical edn by C.A. de Niet, Utrecht, 1996).

Selectarum Disputationum Fasciculus (Amsterdam, 1889).

Other Relevant Works

Bertius, Petrus, Aen-spraeck aen D. Fr. Gomarum op zijne bedenckinghe over de lijck-oratie ghedaen na de begraefnisse van Jacobus Arminius zaligher (Leiden, 1610).

Descartes, René, Oeuvres, 12 vols, ed. by Charles Adam and Paul Tannery (Paris, 1897–1913; Paris, 1964–71; Paris, 1996).

Huygens, Constantijn, De Gedichten van Constantijn Huygens, ed. by J. A. Worp, vol. 8 (Groningen, 1898), pp. 156–7.

Mersenne, Marin, Correspondance du P. Marin Mersenne: Religieux minime, ed. by Paul Tannery, Cornelis de Waard, Bernard Rochot, and René Pintard (Paris, 1945–72).

Molinaeus, Ludovicus, Papa Ultrajectinus: Seu Mysterium Iniquitatis reductum à Clarißimo Viro Gisberto Voetio in opere Politiae Ecclesiasticae (London, 1668).

Philalethius, Irenaeus, pseud. for Abraham Heidanus, Bedenkingen, Op den Staat des Geschils, Over de Cartesiaensche Philosophie, En op de Nader Openinghe Over eenige stucken de Theologie raeckende (Rotterdam, 1656).

Regius, Henricus, Responsio, sive Notae in Appendicem ad Colloraria Theologica-Philosophica … D. Gisberti Voetii (Utrecht, 1642).

Schoockius, Martinus, Admiranda Methodus Novae Philosophiae Renati des Cartes (Utrecht, 1643).

Tranquillus, Suetonius, Staat des Geschils, Over de Cartesiaensche Philosophie (Utrecht, 1656).

———, Nader Openinge, Van eenige stucken in de Cartesiaensche Philosophie Raeckende de H. Theologie (Leiden, 1656).

———, Den Overtuyghden Cartesiaen… (Leiden, 1656).

———, Verdedichde oprechticheyt van Suetonius Tranquillus gestelt tegen de Overtuyghde quaetwilligheyt van Irenaeus Philalethius (Leiden, 1656).

Testimonium Academiae Ultrajectinae, et Narratio Historica quà defensae, quà

exterminatae novae Philosophiae (Utrecht, 1643).

Voet, Paulus, Prima Philosophia Reformata (Utrecht, 1657).

Vogelsangh, Reynier, Breves ac succinctae ad Ludiomaei Colvini Papam Ultrajectinum Animadversiones (London [= Utrecht?], 1668).

Waterlaet, Lambertus van den, Diatribe theologica de jubileo ad jubileum Urbani VIII. promulgatum hoc anno MDCXLI (Utrecht, 1614).

Further Reading

Asselt, W.J. van and E. Dekker (eds), De scholastieke Voetius. Een luisteroefening aan de hand van Voetius’ Disputationes Selectae (Zoetermeer, 1995).

———, ‘G. Voetius, gereformeerd scholasticus’, in Aart de Groot and Otto J. de Jong (eds), Vier eeuwen theologie in Utrecht. Bijdragen tot de geschiedenis van de theologische faculteit aan de Universiteit Utrecht (Zoetermeer, 2001), pp. 99–108.

Bos, E.-J. (ed.), Verantwoordingh van Renatus Descartes aen d’Achtbare Overigheit van Uitrecht: Een onbekende Descartes-tekst (Amsterdam, 1996).

Bunge, Wiep van, From Stevin to Spinoza: An Essay on Philosophy in the Seventeenth-Century Dutch Republic (Leiden, 2001).

Duker, A.C., Gisbertus Voetius, 4 vols (Leiden, 1897–1915; repr. Leiden, 1989).

Groot, Aart de and Otto J. de Jong, Vier eeuwen theologie in Utrecht: Bijdragen tot de geschiedenis van de theologische faculteit aan de Universiteit Utrecht (Zoetermeer, 2001).

Israel, Jonathan I., Radical Enlightenment: Philosophy and the Making of Modernity 1650–1750 (Oxford, 2001).

Knipscheer, F.S., ‘Voetius (Gisbertus), in P.C. Molhuysen, P.J. Blok and F.K.H. Kossmann (eds), Nieuw Nederlandsch Biografisch Woordenboek, vol. 7 (Leiden, 1927), cols 1279–82.

Nauta, D., ‘Voetius, Gisbertus (Gijsbert Voet)’, Biografisch lexicon voor de geschiedenis van het Nederlandse Protestantisme, vol. 2 (Kampen, 1983), pp. 443–9.

Oort, J. van, C. Graafland, A. de Groot and O.J. de Jong (eds), De onbekende Voetius. Voordrachten wetenschappelijk symposium Utrecht 3 maart 1989 (Kampen, 1989).

Ruler, J. A. van, ‘New Philosophy to Old Standards: Voetius’s Vindication of Divine Concurrence and Secondary Causality’, in Nederlands Archief voor Kerkgeschiedenis / Dutch Review of Church History, vol. 71 (1991), pp. 58–91.

———, ‘Franco Petri Burgersdijk and the Case of Calvinism Within the Neo-Scholastic Tradition’, in E.P. Bos and H.A. Krop (eds), Franco Burgersdijk (1590–1635), Studies in the History of Ideas in the Low Countries (Amsterdam and Atlanta, GA, 1993), pp. 37–65.

———, The Crisis of Causality: Voetius and Descartes on God, Nature, and Change (Leiden, 1995)

———, ‘Waren er muilezels op de zesde dag? Descartes, Voetius en de zeventiende-eeuwse methodenstrijd’, in Florieke van Egmond, Eric Jorink and Rienk Vermij (eds), Kometen, monsters en muilezels. Het veranderende natuurbeeld en de natuurwetenschap in de zeventiende eeuw (Haarlem, 1999), pp. 120–32.

———, ‘ “Something, I know not what.” The Concept of Substance in Early Modern Thought’, in Lodi Nauta and Arjo Vanderjagt (eds), Between Imagination and Demonstration. Essays in the History of Science and Philosophy Presented to John D. North (Leiden, 1999), pp. 365–93.

Steenblok, C., Gisbertus Voetius: Zijn leven en werken (Rhenen, 1942; Gouda, 1976).

Verbeek, T. (ed.), La querelle d’Utrecht (Paris, 1988).

———, ‘Voetius en Descartes’, in J. van Oort, C. Graafland, A. de Groot and O.J. de Jong (eds), De onbekende Voetius. Voordrachten wetenschappelijk symposium Utrecht 3 maart 1989 (Kampen, 1989), pp. 200–219.

———, Descartes and the Dutch: Early Reactions to Cartesian Philosophy 1637–1650 (Carbondale and Edwardsville, IL, 1992).

———, ‘From “Learned Ignorance” to Scepticism; Descartes and Calvinist Orthodoxy’, in Richard H. Popkin and Arjo Vanderjagt (eds), Scepticism and Irreligion in the Seventeenth and Eighteenth Centuries (Leiden, 1993), pp. 31–45.

Vermij, Rienk, The Calvinist Copernicans: The reception of the new astronomy in the Dutch Republic, 1575–1750 (Amsterdam, 2002).

Han van Ruler

The Dictionary of Seventeenth and Eighteenth-Century Dutch Philosophers

2 volumes : ISBN 1 85506 966 0 © Thoemmes Continuum, 2003

Source: https://witsius.wordpress.com

--------------------------------------------------------------------------

Voetius was born in Heusden, North Brabant, Netherlands. He studied theology at Leiden, served as a Reformed minister in Vlijmen and in Heusden (1610-1634), and was the founder of Utrecht University, where he served as professor of Semitic languages and theology (1634-1676). His first engagement with mission issues occurred at the national synod of Dordrecht (1618-1619), where he dealt with the question of whether baptism could be administered to children from non-Christian backgrounds living with Dutch families in the East Indies. In 1643 he wrote a treatise on religious freedom. His theology of mission is found in Selectae Disputationes Theologicae (5 vols., 1648-1669) and in Politica Ecclesiastica (3 vols., 1663-1676).

Voetius emphasized that missions are grounded in both the hidden and revealed will of God. Only apostles and assemblies such as synods have the right to establish missions; it is not the right of the pope, nor princes and magistrates, nor companies to do so. The goals of mission are the conversion of non-believers, heretics, and schismatics; the planting, gathering, and establishing of churches; and the glorification and manifestation of divine grace. Mission churches, he maintained, should not be subordinated to the sending churches in Europe.

The period after 1800 saw the growth of interest in Voetius’s missionary thinking. Abraham Kuyper (1837-1920) borrowed heavily from him, especially in the field of apologetics. The synod of the Reformed Churches at Middelburg (1896) decided in favor of “ecclesiastical mission” (in contrast to the William Carey model of mission by means of para-church agencies). Both Johannes H. Bavinck and Johannes Verkuyl made Voetius’s missiology known outside the Netherlands. Johannes C. Hoekendijk at Utrecht University, a fervent opponent of Voetius’s views, considered his emphasis on church planting too akin to Roman Catholic missiology.

Jan A. B. Jongeneel, “Voetius, Gisbertus (or Gijsbert Voet),” in Biographical Dictionary of Christian Missions, ed. Gerald H. Anderson (New York: Macmillan Reference USA, 1998), 708.

This article is reprinted from Biographical Dictionary of Christian Missions, Macmillan Reference USA, copyright © 1998 Gerald H. Anderson, by permission of Macmillan Reference USA, New York, NY. All rights reserved.

First Protestant missiologist

Gisbertus Voetius was born into a noble Dutch family at a tumultuous time in the Netherlands’ history. The Eighty Years War (1568-1648) with Spain was raging, while internally the Royalists, who supported the preeminent leadership of the House of Orange, were deeply divided from those who favored the federal government of the Republic of the Seven United Provinces. In addition, the Reformed faith, which had become the dominant religion in the Lowlands in only a few decades, was under attack from the Arminians. In this environment the brilliant Voetius grew up and, at the age of 15, started his theological studies at Leiden University.

After graduation, Voetius served as pastor in Vlijmen (1611-1617) and in his hometown, Heusden (1617-1634). In 1612 Voetius married Deliana van Diest, with whom he had 10 children. He preached eight times a week and worked tirelessly in his congregation as well as outside, bringing many Roman Catholics into the Reformed Church. He also persuaded the far-reaching trading companies to carry missionaries on their ships. On top of his work as pastor and evangelist, he was a scholar, who habitually rose at four in the morning to study Semitic languages (Hebrew, Arabic and Syriac).

In 1634 Voetius started teaching at the theological school in Utrecht, which became the University of Utrecht in 1636. Besides his heavy teaching load, he accepted the call as pastor in Utrecht. He became known as the “defender of Reformed orthodoxy” and was the theologian of Calvinistic piety, called the Nadere Reformatie (the Second Dutch Reformation, comparable to English Puritanism). He wrote prodigiously: books on theology, textbooks, devotional guides for his students, and above all polemic writings against proponents of Roman Catholicism, Arminianism and Cartesianism. In spite of his full schedule, his fame and his elevated position, Voetius could regularly be found teaching catechism to the poor orphans of Utrecht. He continued to preach until the age of 84, and he remained professor at the university until his death at age 87.

As a young man Voetius first wrote about missions when he was a delegate to the national Reformed assembly, the Synod, meeting in Dort from 1618-1619. Best known for dealing with the teachings of Arminius, the synod covered many topics, among others mission issues. Voetius participated in the discussion of these issues and, on behalf of the South-Holland churches whom he represented, he wrote a recommendation to the Synod. He continued to address mission issues throughout his life. The political developments, the influence of the large trading companies (De Vereenigde Oost-Indische Compagnie, The Dutch East India Company, est. 1602, and De West Indische Compagnie, the Dutch West India Company, est. 1621), and the founding of Roman Catholic mission orders convinced Voetius that the internally divided Protestants needed to establish well-organized mission work. In his writings, he gave a systematic treatment of the theology of mission. Quoting both Roman Catholic and Protestant theological works on mission, Voetius is the first to develop a comprehensive, contextual, and comparative Protestant missiology. His mission theology is formally scholastic and indebted to Thomas Aquinas, but the guide to his systematic-theological approach is Calvin’s dogma of predestination and the latter’s emphasis on soli Deo gloria, for the glory of God alone.

Voetius had a broad understanding of the term mission, namely “everything that happens in order to promote, confirm and reproduce the Reformation, including being sent to East India [Indië, present day Indonesia] and other Oriental countries in order to strengthen the existing churches and plant new churches”.(1) For him, being sent (zending) was primarily about “entering the service of the Word in an institutionalized church” and secondarily, going out into the “heathen world.”(2)

The missiology developed by Voetius is theological and ecclesiastical. Its theological foundation is set forth in the disputation De gentillismo et vocatione gentium: God’s will, both hidden and revealed, is the basis of mission. The hidden will of God is God’s eternal decree by which God has predetermined who will be saved. The revealed will of God consists of the promises of salvation (i.e. Is. 49 and 60), and the call to missions (Matt. 28:19). Mission work needs to be done so that all people will hear about God, in order that those who have been chosen might repent and be saved. Mission work is the means through which God’s goal of saving the elect is reached. Worldwide proclamation of the Gospel is from God, by God and for God. It is truly missio Dei, God’s mission.

The ecclesiastical foundation for mission work is found in the disputation De plantationes ecclesarium, where Voetius uses the following outline:

1. Who sends? (qui sint mittentes)

2. To whom is one sent? (ad quos mittendi)

3. Why is one sent? (ad quid mittendi)

4. Who and what kind of people are sent? (qui et quales mittendi)

5. According to which method and in which way are people sent? (qua via methodo et quo modo mittendi)(3)

Ad 1. God is the one who sends through ordinary and extraordinary means. The twelve apostles and Paul were sent directly and extraordinarily (onmiddelijk en op buitengewone wijze) while other “planters and waterers” from the apostolic and post-apostolic period are sent indirectly and ordinarily (middelijk en op gewone wijze). With this bifurcation Voetius rejected the episcopate’s claim of being an extension of the apostolate of those who are extraordinarily sent. This criticism was not restricted to the Roman Catholic Pope and bishops; all monastic orders, individual believers, rulers and governments, and trade companies who claim the right to send do so in violation of God’s law.(4) The authority to send lies, according to Voetius, exclusively with the true Church, its parish council (consistorie), presbytery (classis) and synods. It is only within the context of the Church that true sending takes place, be it by one local church (cf. 2Cor. 8:23) or by a group of churches (cf. 2 Cor. 2:19) who send their representatives in answer to God’s call. Everything else is unbiblical.

Ad 2. The object of mission was viewed broadly by Voetius. The church must send people to all who are alienated from the church: the unbelievers, the heretics and the schismatics. The unbelievers are the “heathens” – civilized and uncivilized, the Jews (including the Samaritans), the Muslims and the “modern” unbelievers who adhere to no religion, such as the Libertarians, the Epicurists, the Enthusiasts, and the Deists.(5) In his scholastic precision, Voetius also divided “heathens under Christian government” (such as the Laplanders in the north of Sweden, the inhabitants of Taiwan, the tribes of Indonesia and the people living in the coastal areas of Brazil – the latter three under Dutch authority at the time) from “heathens with their own heathen government” (cf. Acts 13:1-2, such as the people from Japan, China, India, Iran, Turkey, etc.). Mission work among unbelievers requires the refutation of their belief system before preaching the true religion. Mission work among heretics finds its biblical foundation in Jas. 5:20, whereas mission work among schismatics is allowed and even required on the precedent of the Council of Carthage which sent representatives to the Donatists in order to bring about reconciliation.

Ad 3. Because of Voetius’ broad definition of mission, his goal of mission was likewise broad. It included such work as the ‘gathering’ (recollectio) of churches dispersed by persecution, the reunification of split churches, the financial support of dispersed, persecuted and impoverished churches and the petitioning of governments to alleviate oppression and to remove obstacles to the expansion of the church. However, the main objective of mission work is – in ascending order – the conversion of unbelievers; the planting of churches among the new believers; and, ultimately, the glorification and magnification of God. The conversion of unbelievers and church planting are not goals unto themselves. These activities are subordinate to the highest goal of mission: soli Deo gloria.